Why didn't I make this my Anime Expo costume?

The following post is going to, in no uncertain terms,

SPOIL THE ABSOLUTE SHIT out of the 13 episode

惡の華/FLOWERS OF EVIL TV anime, and roughly the first 7 volumes of manga it was based on. I spoke

AT SOME LENGTH about the show previously, but that was specifically about the first 7 episodes; this is about the final six, and how it's all shaken out compared to the original comics. So, y'know, if you plan to watch and read the show but haven't yet, go do it. Seriously, go buy it

RIGHT NOW - time's a wasting, and that shipping isn't gonna get any freer if you pick 'em up one at a time.

If you ask me, FLOWERS OF EVIL peaks at episode 10, and that's... not entirely a complaint, I guess. That 22 minute piece is one of the more impressive pieces of unusual televised content I've ever seen, essentially a stilted, self-hating piece of tragedy porn that looks the audience in the eye and says "Yes, you were completely wrong about what this was. Deal with it." The show's glacial pacing picks up for just long enough to revel in what makes this story so goddamned interesting to start with, and finally comes full circle with it; Nakamura's fascination with Kasuga was her misunderstanding that his impulsive, selfish nature hid something deeper. Something dark and terrifying that threatened the dull, crushing normalcy of her miserable life. But was she right? Did she ever really have a partner in Kasuga?

When Kasuga is stripped of everything, forced to choose between justifying the love of the girl he had a romanticized crush on and the girl who challenged his belief in everything... he chooses neither. He breaks down in tears, admitting he doesn't understand a goddamned word of Baudelaire, and just convinced himself his pseudo-intellectual fascination with classic literature was a way to convince him that he's not just as ordinary and boring as everyone else. The entire show to that point had - to one degree or another - been our lead character (I refuse to call him a "hero") trying to figure himself out whilst simultaneously wrapping himself in layers of complicated, pretentious bullshit, to the point where even

he believed it. What does Nakamura do with this moment of unexpected clarity? She, quite literally,

THROWS IT BACK IN HIS SNIVELING FACE. And I was overjoyed.

Nakamura's quest to find another emotionally shattered sociopath to share her miserable crawl towards oblivion has failed, and in the end, Kasuga's unexpected, grotesque honesty has cost him the respect and affection of both women in his life. It's an emotionally devastating sequence - one designed to somewhat cleverly undo a lot of the seemingly valid criticisms viewers might have had until that point about the story being pretentious (as opposed to the characters

within the show - creating a character with unlikable traits doesn't mean the author has created an unlikable piece by accident), and it proudly wears the whole concept of Flowers of Evil for the world to see in both the most blatant, and amusing, visual possible. Yeah, it's a bit on the nose, and yes, it borders on approaching the very ideas the story proper is rejecting of pretentious wankery actually meaning anything.

And y'know what? I fucking loved it, because it's

earned that brief moment of self-indulgent symbolism. The most obvious point of comparison the TV series had drawn up to this point was the bizarre, slow-burn films of surrealist mastermind David Lynch, but Lynch worked in nightmarish imagery specifically to explore the inner workings of the human mind in exaggerated ways, meaning that - for example - "The Baby" in

Eraserhead is very real, at least insofar as

anything in that film is. When faced to cop to that uncomfortable level of clarity, Flowers of Evil quickly and violently rejects the un-reality of its initial presentation; Kasuga's own visions of the "Flowers" watching his evolution into a deviant are then regulated to his dreams, and the only glimpse of the "Other Side" appear in the hastily scribbled notebooks that the characters themselves have created.

That overbearing sensation of discomfort and broken narrative doesn't change, but the subtle, at times almost supernatural underpinnings - suggesting that the story is, somehow,

more than it really is, to the point where Mrs. Kentai was curious if the series had supernatural elements at play - basically evaporate with Kasuga's inflated sense of self-importance. Part of me wishes the series had actually taken it a step further - filled the whole proceedings with even

more insane internal-visuals leading up to Kasuga's breakdown, be they blatantly false (like him seeing Saeki as the Virgin Mary) or merely over the top (Nakamura's "So Anime!" bit of skipping through a pulsating rainbow backdrop) - but, as ever, I find that what works in the show just wasn't focused on quite enough to draw the comparisons I want to. In effect, the Flowers of Evil TV series reminds me of a great David Lynch movie... but, I'm not convinced it's as

good as a great David Lynch movie.

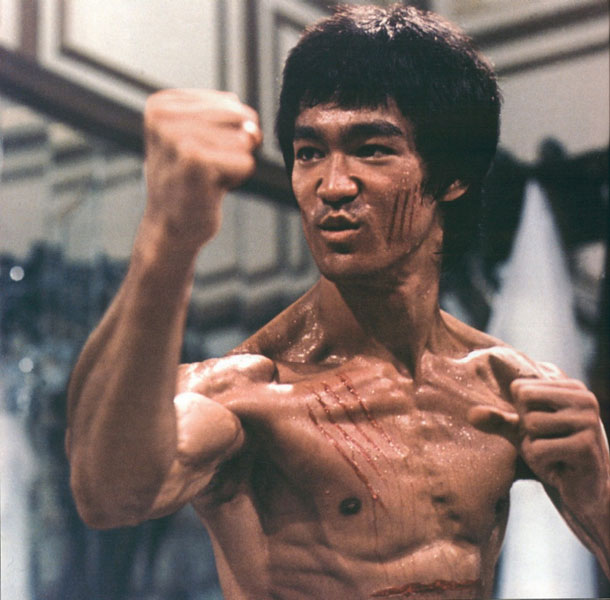

Whatever you think this means... it's actually far worse.

Having recently read way too much chatter from viewers who either were emotionally unable, or consciously unwilling, to see the largely clear-cut ideas presented in the narrative, I'm going to throw out my interpretation of what makes this story so fascinating, and a lot of it comes down to the dynamic of power; Nakamura assaults Kasuga and forces him to wear Saeki's gym clothes. Kasuga doesn't agree to it, but he doesn't actively strike Nakamura, either. He's a coward. He's a sniveling, unsure ball of confused adolescence afraid that Nakamura will expose his "sin", and when it's over Nakamura sits on top of him, panting, looking - for lack of a better term - satisfied. This scene is an inversion of sexual assault as it's typically known; she dwarfs him emotionally, and the domination of his body follows suit. She's overpowering and even emasculating him. She makes Kasuga her indisputable bitch without needing to penetrate either of them, because sex isn't really a part of her agenda - not directly, in any case; ever the literal symbol, Nakamura strips Kasuga of his pretenses and exposes him for what she thinks he really is: A sexually frustrated, fetish-clothing obsesses deviant.

When she makes Kasuga admit to being hard and touching himself while wearing them, the shaky validity of her assertions are somewhat irrelevant - what matters is she sees through the romanticism that Kasuga can't, again, because he's bought into his own sense of intellectually inflated nonsense. Arguments that Kasuga could have fought her off or that he may have secretly "wanted it" are missing the whole point of their characters; interpreting it as anything but one character exerting the emotional power the other has granted them is stretching quite a bit, as is questioning how creepy this dynamic could have been had their genders been reversed. As I said last time, the inversion - the switching of gender and power roles - from a hundred different rape-fetish anime and eroge in the pattern of

Isaku and

Yakin Byoutou was the whole POINT of this relationship, which might be possible to do, if you haven't whacked it to countless Isaku knock-offs in the last decade, and I wouldn't be surprised if a lot of the people who find themselves uncomfortable with this idea are doing so out of a fundamental lack in understanding that this scenario is perfectly normal for "rough" minded Japanese cartoon pornography. It'd be like trying to discuss

Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon without having seen a single Jason or Michael Meyers movie - you

could, sure, but why would you even want to? Someone's telling you a joke, and you don't have enough background in the subject to follow it.

Episode 10 is the turning point, the moment Kasuga realizes he's fundamentally a blank slate; he doesn't really know why he exists, and he's been selfishly aggrandizing Saeki whilst lying to himself about his "wicked" personality so he didn't have to face the fact that he was, like everyone else around him, just a pathetic creep with selfish desires. Episode 11 leaves him still drawn for reasons he doesn't understand to Nakamura - the girl who abused him, who humiliated him, and who destroyed his illusions about himself - and the next two episodes are devoted to Kasuga both trying to apologize, and in the end, finally understand Nakamura. He succeeds (on some level, anyway) when he reads through Nakamura's uncomfortably serial-killeresque diary, and is heartbroken by what he finds; the realization that she only wanted to help him on her own twisted terms - a fellow freak trying to drag one of her own out of the closet, and one that increasingly found little worth being excited for when she no longer had the purpose of helping a fellow tortured soul lick his own wounds. Without the aide of another 13 episodes to work with, the Flowers of Evil TV series essentially ends with Kasuga finally accepting that if he has to be something, it might as well be what he always thought he was: He lives the lie of being a deviant until it becomes his reality, and he finds the terms to do it that finally give him the responsibility he so openly threw away when he tried to deal with Saeki's emotional baggage. In short, the TV series ends with Kasuga realizing his own worth and becoming a man... he just does it in the single most destructive way possible by deciding to be Nakamura's vassal.

There's a single moment in Episode 13 that strikes a chord in me I had to ponder for a moment: When Nakamura comes into her room and finds Kasuga in tears reading her diary, there's a moment where she grins, the same way she would when she'd torment Kasuga... but why?

Why is she elated by this act of betrayal? Because whether or not Kasuga realized it, he had done to Nakamura what he had previously done to Saeki; he invaded her privacy in a moment of perverse weakness, and in very awkward terms has proven that Nakamura was now the object of his affections.

Of course, he was still a shit-bug reading her diary after having proven to be far less an individual than she'd previously expected, so she flipped out anyway. Hard to blame her, all things considered. But this in turn begins one of the more fascinating aspects of these two characters, as they enter into an increasingly uncomfortable, not-directly-sexual D/s relationship: The whole way through, Kasuga continues to do things that make Nakamura proud - namely peeling off his "skin" of his own accord and carving out a portal to "The Other Side" for her, and Nakamura continues to - as she sees fit - both nurture and tease him, not unlike the way most people would treat a dog they were particularly fond of. Kasuga is clearly physically attracted to Nakamura, but never tries to get any closer than Nakamura's own terms dictate that he be allowed; she even uses him as furniture and flashes fleshy bits of her body to establish that he's still in command, acknowledging that part of Kasuga's true self involves desires she herself is satisfied to ignore. Before "The Other Side" is destroyed, there's some question as to if Nakamura's attitude towards physical attraction is as non-existent as she suggests, but that quickly becomes irrelevant when her fun is interrupted, setting their relationship back to square one without any reason for Nakamura not to pummel the poor kid into submission.

This comes to its thematic high mark when Nakamura physically tears away at Kasuga's flesh, and gives her final order... clearly out of his depth, Kasuga loses his shit for a moment, but agrees to Nakamura's slightly more dramatic - and no less shocking - demands to end the contract on her own terms. Kasuga stands his ground and becomes what Nakamura thought he was, even at the cost of his own being.

Boom goes the dynamite.

This relationship's core concept gets far more uncomfortable when - in the manga, at least - Saeki looks at the dynamic between Kasuga and Nakamura and tries to emulate it herself. Saeki is a far more interesting character than some people give her credit for; yes, there may be an undercurrent of perverse wish-fulfillment in seeing her not reject Kasuga for his previous actions, but she's a young girl, and for the first time she feels like someone has acknowledged that she

exists - that she's a fully formed, independent, beautiful person capable of making others want and love her. She sees Kasuga's innocent worship of her as a vindication of her own existence - itself seemingly a complicated dance for her parents sake she's sick of keeping up - and when Kasuga breaks up with her, she doesn't see it as the boy trying to protect her; she sees it as having somehow "lost" to Nakamura, the only person Saeki sees as capable of not giving a single fuck about what others think of her. Saeki's sense of self-worth are built entirely on her being an ideal - not an actual person - and she becomes infuriated with Nakamura's ability to be everything she's not, merely by not caring about everything she does. When she's refused by Kasuga as she offers the last thing she feels she has to give - her physical innocence - she ignores him and takes him by force, which likely isn't that hard to do with a sexually amorphous 14 year old boy. (Hell, I

still get boners when they're least appropriate, and I'm at least twice Kasuga's age.)

This is important on two levels, one I'm curious if some readers glossed over; the most obvious point is that she physically dominates Kasuga and then shows off the bloody proof to Nakamura, who basically just laughs and asks why she should

care. Again, Nakamura's focus on Kasuga having sex had nothing to do with her wanting to have sex with Kasuga, so her reaction - at least, the one she spoke of out loud - is that it was irrelevant, and that Saeki could fuck the little shit whenever she wanted. The more subtle fallout is the fact that, when Kasuga worked up the nerve to ask Saeki out in the first place, he specifically asked for a platonic relationship. That's right, he literally asked for a non-sexual romance so he could keep this pure, romanticized image of Saeki alive in his head, and she shatters it by physically violating him. Forcing herself on him is bad enough; the fact that the act contradicted the one thing he ever requested of her when they entered in their thinly formed relationship makes it so much worse, though.

Why does any of this this matter, though? If Nakamura doesn't care, why does she become so frustrated afterward? This is because Nakamura took control of Kasuga not to demean him, but to peel off the layers of his artifice and find the beast lurking beneath; she tormented and abused him specifically with the goal to help

him. Saeki is far less altruistic, and merely takes control to further her own sense of self worth; Kasuga quickly became a pawn to show Nakamura that she still "won" a competition she never understood to begin with. Saeki used Kasuga's body just as Kasuga used his fantasy of Nakamura, projecting an idealized romance on their own selfish terms without ever really acknowledging that the other was an actual human being. By comparison, Nakamura turns out to be the compassionate woman in this unusual romantic triangle; she certainly took enjoyment in watching Kasuga squirm, but she only did it because she legitimately thought it would make him happy to begin with. Granted, Nakamura's

still a crazy bitch, but at least she was a sincere, well meaning kind of crazy bitch. In the end, the physically violent sociopath could be the most honest and emotionally cohesive character in this whole affair... how's

that for a depressing snapshot of adolescence?

But to get back to the TV series for a moment, the final episode did something...

interesting. I can't call it good, because the grotesquely slow pacing that embodies the show made it a requirement in the first place, and while I understand the concept behind pacing this like an arthouse feature there's too much ground to cover to justify it. But I can't call it bad either, because the very nature of the beast is only interesting BECAUSE the rest of the show has been so intensely argumentative to the tone of it. I'm talking, of course, about the show's three-minute long flash-forward, layering out of context dialog and quick glimpses - some of them merely a second long - of unprovoked violence, implicit sexual assault, and the ultimate plan to reach the Other Side.

The only way I find I can describe this version of Flowers of Evil is if the legendary finale to Martin Scorcese's

Taxi Driver had been a series of uncertain, fast cuts interspersed through the footage of Travis Bickle waking up in the hospital bed, not really answering the burning questions of what went down during what was the film's ultimate act of violent catharsis, other than to leave the impression that "shit got real". Taxi Driver might not seem like a particularly appropriate comparison piece, but both Bickle and Nakamura are young, angry people who project their frustration onto the world around them until they both resort to drastic measures;

if Flowers of Evil has any catharsis, it's all buried in that churning, indistinct montage, promising the ultimate conclusion of the show's antiheroes without actually explaining a goddamned thing. Part of me is overjoyed they found a way to acknowledge this material at all; the rest of me wishes they had simply sped the pace up to 2X and we could have actually gotten to see that footage play out in real time. I'm slightly jealous of Justin Sevakis' recent comment summing up that there's an excellent feature film to be made from the 13 episodes of raw footage, which is honestly the only way I could see the final stretch of the manga's story arc being animated by way of a 90 minute rotoscoped feature.

D'aw! Look at all the emotional baggage!

At the end of the day, Flowers of Evil - the TV adaptation, at the very least - was made to please a select few, but raise the ire of everyone else, and left plenty of potential fans in the dust to approach the uncomfortable subject matter on its own terms, flawed as they could be. Mrs. Kentai cringes every time she sees me watching it, and when faced with the reality that the "cute" designs of the original manga are no worse at expressing the same ideas and sentiment as the intentionally distorted rotoscoped visuals of the TV series, I find myself unable to argue that they were 'better' than a typical anime art style - more unique and conversation worthy, sure, but I'm not convinced they were necessary to tell the story itself, lest the original material would crumble under its own adorable nature. While there are brilliant

moments peppered through the show - Nakamura stripping Kasuga, the destruction of the class room, even the way the wet pages of Baudelaire being thrown in Kasuga's face were handled - at the end of the day, the decision to create a totally unique and polarizing art style served to grab people's attentions and establish that Japan is far from finished trying to innovate TV animation, but not too much else. I'm fine with this show looking, and even unfolding the way it does; it certainly grabbed my eyeballs, and it's caused ten times the discussion that the thematically similar teen-romance deconstruction epic

School Days ever did in the English speaking world. (And that's not entirely fair, because School Days is fucking

brilliant.)

And therein lies the real rub, doesn't it? Fans of the original manga expected a more or less straight-up adaptation of the original manga, which director Nagahama rejected as being pointless; the original work is fine the way it is, and he suggested creator Oshimi adapt it as a live action series. A

VERY INTERESTING TRANSLATION of an interview with these two men to promote the TV series reveals some very interesting methodology behind the show's creation, and in the interest of exploring how this show came to be, here's the summary in full:

In short (note that this is a quick & dirty summary):

- At first Nagahama (the director) refused the offer to direct the adaptation, because he thought that simply turning this manga into a pretty, clean-looking anime would be pointless. He says that he believes that when the mangaka draws this story he's seeing something "else" which he expresses as a manga. So there would be no point in simply presenting it in animated form, at that rate you might as well just read the manga and be done with it.

- He thought if it was to be adapted at all, it should be done as a live drama. When he was offered the job the second time, he pitched the idea of using rotoscope. He was aware that the result would be different from the manga.

- Oshimi (the mangaka) says Nagahama is right about the way he creates the manga: the original story is something that exists in his head, and he draws what he sees in his mind. So basically the anime and the manga are two different versions of the story that exists in Oshimi's head. By the way, he was also aware that due to the rotoscope the anime would look different from his work, and he thought it was an interesting idea.

- Oshimi also says that he thinks Nagahama has a very deep insight into the story, and firmly believes that he's taking it in the right direction. He also very much approves of Nagahama's wish of the anime leaving the viewers with a scar.

- Oshimi was pretty much "in" on the whole thing, they tested the rotoscope method on him.

- The interviewer asks about the impact the visuals would have on viewers, and Nagahama says he's well aware that a lot of people will go "what the fudge" and "this is gross," "I hate this, I'm not watching this." But he's pretty much okay with that, too, because he thinks it's fine as long as it leaves an impact on people. Viewers may dismiss it right away, but some may check it out later and find it interesting, or they may come across the manga, recognize the title, and read that.

- Oshimi says that he once got a fan letter from a high school girl who wrote that when she read the manga in middle school she thought it was stupid, but she tried to read it again when she was older and she found it very good. Nagahama says that this is what he's going for, to leave an impact, even if it's negative. He's trying to create something that one can't just ignore or dismiss.

- Oshimi also says that the anime has many scenes that he wishes he would've drawn the way they are in the anime, for example a scene with Kasuga and Nakamura in the classroom.

- Also, he confesses he's writing the manga with the intention of murdering the readers with it (metaphorically, of course), thinks the anime is doing the same, and relishes the idea of the viewers getting slaughtered, jokingly of course. (lol #1)

They leave the following messages to the fans:

- Oshimi: He guarantees that those who feel very strongly about Aku no hana will enjoy the anime. However, chara-moe types, those who go "Nakamura-san, unf unf" will probably feel betrayed. (lol #2)

- Nagahama: Since it's so different from the usual anime, he can't say that everyone will love it. But those who watch the first episode and think "I want to see more" will not have their expectations betrayed.

In other words, the two architects behind the TV series went out of their way to craft something they knew the average anime fan would reject - from the sound of it, the cute art style in the original manga may well have been something the publisher requested, rather than something Oshimi himself was particularly into. Without casting judgment or even saying whether or not that's a "good" idea, I have to admit, I admire the balls that decision made, and for sticking to it once made. I'd *LOVE* to have seen the pitch they made to investors, "No, really! The show will be so hated by the fans of the manga that everyone who HASN'T read it will be so curious they'll check it out!" One wonders what might have been in the hands of a less defensive Nagahama...

Not sure if thrilled, disappointed, aroused, or all of the above...

Was it right to craft such a different, "ugly" style just to draw attention to the original manga? Well, there's now a stack of Vertical published books on my shelf, and if the point of the TV show was to cause enough controversy to get people to check the original material out, mission fucking accomplished. I'm glad to have these if, for no other reason, I can force my wife to look at the twisted, depressing, and yet not entirely unsympathetic relationship between these three central characters and understand

why I willingly sat through four minutes of two characters walking in total silence. To be fair, even that stretch of silence serves both a narrative and a thematic purpose... it just drives me insane, watching such a fascinatingly ugly story drag its feet before it can

really dive into the deep end where it belongs.

While I'd argue the semantics 'till I was blue in the face if I cared more, a friend of mine - who loves the show harder than I do - claims that it's "not anime", and really shouldn't be judged by the same metric any other piece of contemporary Japanese cartoons should be. It's so far removed from anything Japan typically creates, or even likes, that its only reasonable company are pieces of experimental French animation - . It was a show literally created as a raised middle finger to expectations and even to the audience that would typically lap this up like 2D crack, and - particularly from a director who's made some popular and "traditionally" beautiful animation - it's a bold,

crazy move. I respect it, even. But at the end of the day, it's - by and large - the thing I find myself torn over. The pacing I can deal with. The soundtrack I've come to love. But that sloppy, inconsistent rotoscoping? I've finished the show and I

STILL don't know if I love it or hate it.

I won't praise Flowers of Evil for being "deep", because doing so would just make me a shit-bug: What I will say is that is successfully crafts a three dimensional portrait of an unconventional love-triangle/tragedy, and while the anime totally fails to cover the entire breadth of the story itself, it does a very unconventional and fascinating job of presenting those ideas none the less. It's a malformed experiment, released to the public without the budget or episode count to fully work... but if you can watch the final minutes of episode 7 and not think that alone was worth trying, I don't know what more could convince anyone.

In the end, Flowers of Evil is a totally unique, fascinating... but imperfect experience. It captured my fancy, it crushed my soul, and in the end, it gave me a lot to think about - not by way of piling in unnecessary symbolism, but by brutally rejecting it, and asking the viewer little more than to accept that broken people can simply

be broken. Much like the grim, fatalistic relationship its lead cast shares together, there's something simultaneously hideous and beautiful about it, and my only wish was that this had been well received enough for the full storyline to run its course to the end of the Summer Festival. (That post-time skip bullshit afterward can fuck

right off, thanks. Nope, I don't even care what Oshimi has up his sleeve, it should have ended at the Summer Festival.) But this it how it ends... not with a bang, or a whimper, but with confusion, fear, loathing and the promise of both more and nothing in the same shuddering caw. If nothing else, Flowers of Evil ends on the same uncomfortable and uncompromising note as its young antagonists; angry, alone, and unsure of what will happen now that he realizes how far past the lines of normalcy he's treading, and can't turn back without severe consequence. It's not exactly

fun, but perhaps it's a fitting blue-ball finale for a story obsessed with the bleak hopelessness of adolescence. Whether or not you find that very notion to be a pretentious bag of bollocks is, I suppose, a personal call.

"Attention, shit-bugs!"

Fans of unusual, challenging animation as forms of expression are absolutely recommended to check out the anime on... ugh, Crunchy Roll, and pick it up on DVD/Blu-ray whenever Sentai Filmworks gets around to releasing it. For those curious to explore the diseased, violent mind of Japan's outliers in love - but aren't sure if they can take Arthouse pacing and generally unpleasant art design - might be better off buying Vertical's release of the original manga. Frankly, I'm in for both, but hold no delusions that most viewers or readers will even

want to experience this more than once.

Do forgive this bit of poorly edited self-indulgence: I'm very much in the mood to post something more interesting than yet another complaint about Fist of Fury, and I'd rather post this while it's somewhat fresh and throbbing before I file it away forever. Also, my fucking smoke alarm's battery died recently, so sleep has been... hit or miss, for the last two or three days.